Fudge basics

Ingredients

“Real” fudge is nothing more than white sugar, brown sugar and, you guessed it, cream. A bit of vanilla or maple extract for flavour, nuts if you desire, and you have that sweetest of sweet treats found in so many Canadian homes. Other ingredients can be added depending on the recipe you’re working with: icing sugar, maple syrup, corn syrup, evaporated milk, marshmallows. Ricardo even adds white chocolate.

Desired texture

What do you look for in a piece of fudge? It should hold together well without being too hard and, above all, has to be melty and silky in your mouth. It’s the size of sugar crystals that makes the knees of fudge lovers buckle…the smaller the crystals, the less they are perceived on the tongue and the more the fudge tastes smooth and creamy. Cooking, and beating after cooking, is the key to successful fudge.

Cooking

Cooking is necessary to dissolve sugar crystals and to evaporate part of the water in the cream. The length of this step has a direct impact on the firmness of the fudge. As water gradually evaporates, sugar is concentrated and the temperature of the mixture rises above 100°C (212°F). If there is too much evaporation, when the cooking time is too long, there will not be enough water left in the fudge and it will be too hard. Conversely, if the cooking time is too brief and there is not enough evaporation, too much water will remain and the fudge will be too soft. A temperature of 112°C to 114°C (234°F to 237°F) must be maintained. This will ensure the fudge has the ideal concentration of water and sugar.

Fudge is difficult to make. Don’t rely on recipes that tell you to boil the fudge mixture for a specific amount of time. There are too many unknowns to set an exact time. Cooking time depends on the size of your pan—the bigger it is, the more evaporation will occur—plus the heat intensity or power level of your microwave. The best way to check if it’s done is to measure with a candy thermometer or do a cold water test.

Online store

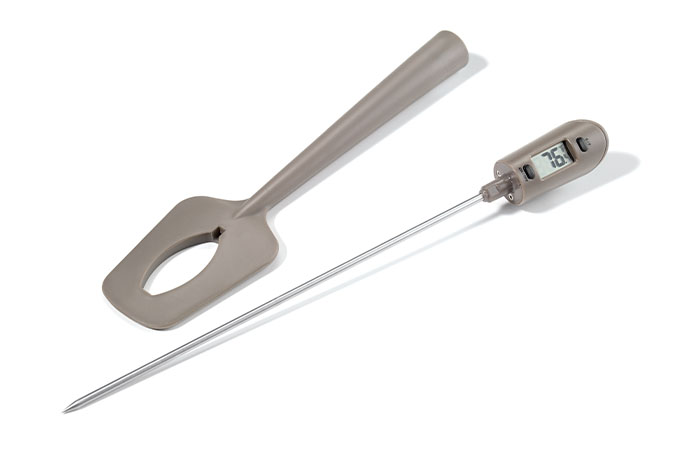

Silicone Thermometer Spatula

Valuable tips for successful fudge

1. Don’t stir during cooking

Fudge can be cooked on the stove or in the microwave. The advantage of using a microwave is that the mixture will not stick to the bottom of the pan during cooking. In both cases, sugar and cream must be brought to a boil by gently stirring, then—and this is very important—refrain from stirring again throughout the rest of the cooking process. Sugar crystallization causes a chain reaction: If a crystal is present in the mixture, other sugar molecules will attach to it and the mixture may seize and become grainy.

2. Avoid crystallization

During cooking, sugar crystals can stick to the sides of the pan. If you stir the mixture, these crystals could fall in and crystallize a part of the sugar again. To work around this issue and dissolve all crystal traces, brush the sides of the pan with a brush dipped in water at the beginning of the cooking process.

3. Let cool before beating

After being cooked, the sugar must crystallize again to create fudge. This stage will determine the size of the sugar crystals. The sugar should ideally form small crystals that are barely discernible on the tongue. To achieve this, let the mixture cool for 15 minutes before beating it. It will thicken as it cools, so when you beat the mixture, sugar molecules will have a tough time clinging to one another (it’s like trying to swim in molasses!). The result: crystals that form will stay small. Experience has shown that you should beat the mixture when its temperature ranges from 43°C to 45°C (110°F to 113°F), which normally occurs 15 minutes after the pan is removed from heat. The fudge is warm, but not burning hot.

4. Beat the mixture

After letting the fudge cool, it’s time to beat it. It is important to stir constantly with a wooden spoon until the mixture starts to thicken and its surface starts to look dull or matte. Now is the time to stop beating and pour the fudge into a mould. Another tip: Do not scrape the sides of the pan or the spoon used for stirring. They are often covered with a grainier layer of fudge.

- • Use a heavy pan that distributes heat well or the mixture may stick during cooking. This advice does not apply if you are making fudge in the microwave.

- • Brush the sides of the pan with a wet brush at the beginning of cooking to dissolve sugar crystals stuck to the sides.

- • Never stir the mixture during cooking or sugar could crystallize again. The mixture may seize and become grainy.

- • Use a candy thermometer or conduct a cold water test to check if the fudge is done. Do not rely on the cooking time indicated in your recipe. The fudge is ready when a candy thermometer reads between 112°C to 114°C (234°F to 237°F) or the mixture forms a soft ball in cold water.

- • Let the mixture cool before beating. The temperature at this point should be 43°C to 45°C (110°F to 113°F). The fudge should be warm but not burning hot.

- • Stop beating when the surface of the mixture starts to look dull or matte. Pour immediately into a mould that has been buttered or lined with parchment paper and let cool completely.

The cold water test

Even without a candy thermometer, you can still check if the fudge is cooked by doing a cold water test. Drop a piece of hot fudge into a glass filled with ice water. It should form a soft ball that can easily flatten between your fingers. Repeat this test every two minutes, each time using a clean spoon, until the fudge has the desired consistency.

Ready to make some fudge? Here are a few recipes to satisfy your sweet tooth:

Maple Fudge

Maple Syrup Fudge

The best

Maple Fudge (The Best)

ALLERGY-FRIENDLY

Dairy-Free and Nut-Free Sugar Fudge